| Photo of the month – December 2017 |

[German version] |

Torpedo tubes ready to fire

23.4 tonnes of steel pipes, some "nested". Pipes that are placed inside each other in order to save space when loading are referred to as nested. This loading method only makes sense under very limited circumstances, namely:

- if the pipes are all the same length or

- if the pipes on the inside each protrude a little to the rear from the outside pipe and

- all the pipes can be secured as a 100 % tight fit in the direction of travel.

- if the pipes on the inside are prevented from rolling back and forth by sandbags or something similar, thus eliminating the dynamic aspect of this loading strategy.

It is only possible to transport nested pipes within these very narrow constraints. Otherwise, it is not possible to secure the pipes that are on the inside, meaning that pipes must not be transported in this way.

Figure 1 [Florian Huber]

When this consignment was loaded, pretty well every conceivable mistake was made. Some may find nothing unreasonable about this photo, after all, intermediate dunnage with pipe wedges has been placed, and we can see some tie-down lashings. Taking a closer look at the front right of the top row, we see that 3 pipes have been placed inside each other. And if we really study the picture, we can see that the top-right "trio" of pipes is not quite aligned with the pipe it is resting on. The rear part of the pipe is pointing inwards slightly and the front part is pointing outwards and to the right a little.

Figure 2 [Florian Huber]

Figure 2 shows the full extent of the nesting. Here we also get some way towards answering the riddle as to why the top-right pipe or trio of pipes is somewhat crooked. The rear "pipe clamp" is broken and the pipe has already slipped down between the pair of pipes underneath. This movement has caused the front part of the pipe to twist a little to the right of the vehicle. We can see wooden wedges in the nested pipes to prevent the inner load from rolling back and forth in the outer load. These are dynamic forces that are entirely incompatible with safe transportation. We can also see water from melting snow running off the loading bed. On some other photos, considerable amounts of snow can also be seen in the nested pipes. In plain terms, pipes covered with a significant amount of snow have been inserted in each other. Anyone who has ever enjoyed sledging with a sledge with steel runners in winter has a good idea of the effect of snow on the coefficient of friction. We will talk about this more when we come to the securing method.

Figure 3 [Florian Huber]

But this fiasco appears to have no end. Indeed, this consignment tops almost everything we have looked at before. The groups of pipes loaded on the second layer have been placed at a distance of more than 60 cm from the end wall. This guarantees that if the load slips, it can generate enough kinetic energy to penetrate the end wall and possibly even the driver's cab. The Photo of the Month from February 2003 gives a vivid illustration of what can happen in accidents such as these. Nested pipes were also involved in that case. Pipes that were obviously secured equally as well as the ones in today's photo.

Figure 4 [Florian Huber]

Anyone with any sense for the weights involved in this consignment might have looked at Figure 1 and guessed that the pipe clamps (intermediate dunnage with pipe wedges) were rather on the small side. This consignment provided the evidence several times over. This lumber probably broke or at least cracked as soon as the pipes were placed on it. We can also clearly see the residual snow lying on the wood and steel and which is, at the very least, not having a positive effect on friction.

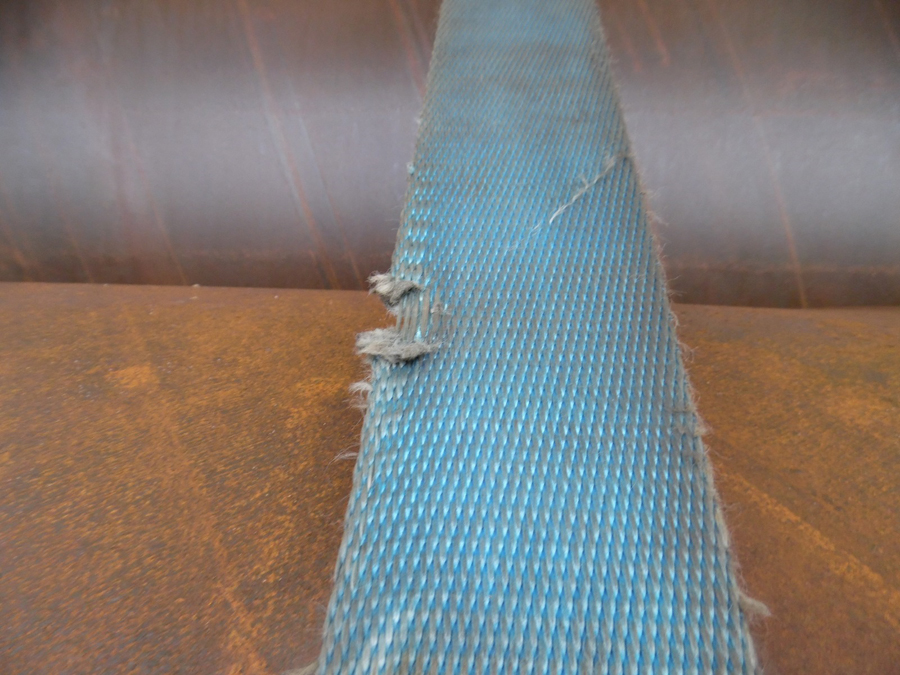

Figure 5 [Florian Huber]

Figure 5 shows the inevitable result. A gap appeared between the pipes and the pipe wedges, which could no longer hold the pipes. Incidentally, this pipe wedge was also cut incorrectly, but we didn't want to go into such minor "blemishes" here. Nevertheless, we will include the cutting pattern for pipe and crate wedges at this point, in the hope that there are enough people in the world who generally want to do their job professionally and well.

Load securing wedges are divided into three categories:

- Pipe wedges for holding cylindrical loads

- Crate wedges for holding rectangular loads

- Driving wedges for filling gaps.

Wedges must be used in such a way that nails can be driven into the side along which the grain runs (3). Nailing into the end grain (1 or 2) can lead to cracks when driving in the nails or as a result of jolts during transport. Experience shows that the withdrawal resistance of nails in end grain wood is half as much as on the grain side. Pipe wedges are used with cylindrical or round cargoes such as vehicle wheels, pipes, rollers, etc.

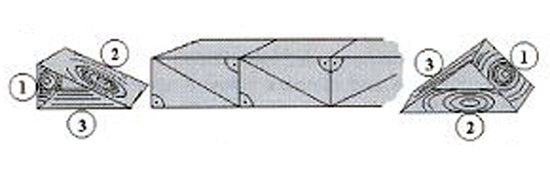

Diagram [GDV]

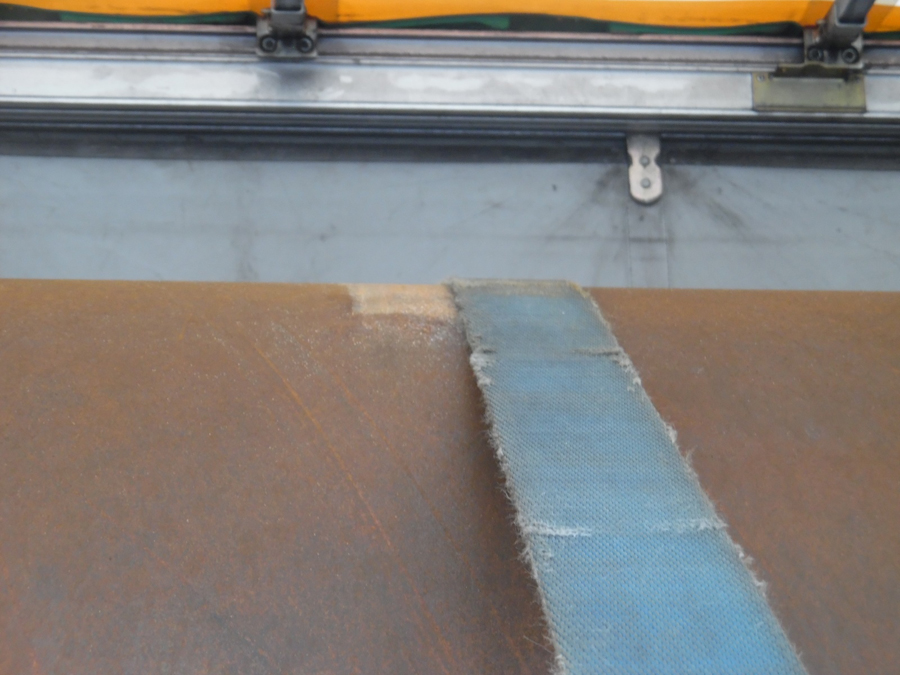

Figure 6 [Florian Huber]

We don't want to go into more detail about all the things that were probably not considered when this load was secured. But, at least, 4 tie-down lashings were used, and according to the labels on the ratchet handles the belts were supposed to deliver 750 daN of pre-tensioning force. Three of these belts show signs of damage that may not make them absolutely fit for scrapping, but very nearly do so. This lack of care fits perfectly into the catastrophic overall picture. It is probably better not to go into the level of friction between steel and wood or steel and steel when they have deposits of snow on them. This attempt to secure the load was no more or less than a catastrophe!

Figure 7 [Florian Huber]

It is only logical that Figure 7 also shows a belt with considerable signs of wear and tear, and the steel clearly shows that the pipes have already moved significantly. Given that all the photos have clearly been taken from the right of the vehicle, this photo shows that the pipe has, for whatever reason, slipped backwards a little. This is further proof that securing a load to the rear is not in vain and is certainly not a free bonus.

So how can a cargo like this be loaded safely?

If the pipes really do have to be nested, i.e. if they are to be transported inside each other, the entire load-securing strategy has to rely on an end wall or reinforced end wall. Even if the outer pipes are loaded on anti-slip material, the inner pipes cannot benefit from this friction. This means that distinct approaches to friction need to be adopted. Put simply, this means that a coefficient of friction μ of 0.6 can be used for the calculations for the four outer pipes, thanks to the anti-slip material. For the inner pipes, however, a value of 0.3 will need to be taken, as the material pair is rusty steel on rusty steel. It is entirely beyond our imagination how snow-covered pipes can be responsibly loaded when nested.

The pipes must be of equal length and have to be level at the front so that they can be restrained directly by an artificially reinforced end wall or a sturdy beam construction supported by belts, chains or wires. The fact that the pipe clamps were far too flimsy in this case should have become obvious to anyone by Figure 4 at the latest. There are clear guidelines as to how much pressure softwoods, such as the spruce or pine used here, can withstand. Lumber must therefore be dimensioned accordingly. There is at least something positive that we can say about this consignment at this point: We noticed that the pipe clamps were made from lumber with a rectangular cross section. Another mistake that could have been made would have been to use thicker dunnage with a square cross-section, which would also make it likely that the load would roll in the direction of travel. If the pipes are nested and loaded, effective direct securing must prevent any movement to the rear as well. This is only possible if the pipes are all of the same length, or if each nested pipe protrudes a little further to the rear, so that it can actually be secured directly or as a tight fit, albeit with a considerable amount of effort. Beyond this, we always have a bad feeling when we see such loads secured only with tie-down lashings. Particularly as loop lashings do not involve much more work, provide a similar tie-down lashing effect and are at least far safer when it comes to securing the load to the sides and relieving the pipe wedges and pipe clamps – effectively with no extra outlay.

It goes without saying that we recommend that these pipes should be secured individually using sturdy pipe clamps, friction-enhancing intermediate dunnage, loop lashings to enhance securing to the sides and, if possible, a direct securing strategy which prevents the pipes from moving forwards and backwards.

Anyone who has a look at the Photo of the Month from February 2003 will recognize the danger that lies dormant in loads such as this.

Your load-securing columnists wish you all safe driving and a happy Christmas!

Back to beginning