| Photo of the month – November 2016 |

[German version] |

Synchronized slippage – or the big, bad spook of technology

According to the driver, this accident happened when his vehicle was forced to brake by the emergency brake assist system. This happened because a vehicle pulled in just in front of him:

Figure 1 [Wolfgang Jaspers]

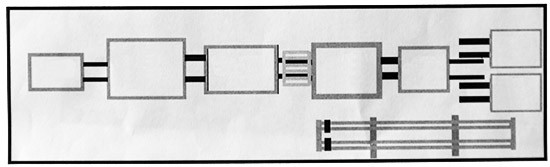

Our immediate emotional reaction may be to blame an inconsiderate driver whose driving caused such immense damage on the vehicle behind. And it is true that he caused the emergency brake assist system to brake the vehicle sharply. And as a result, the load, which comprised material handling equipment (forklift trucks and electric pallet trucks), slipped forwards. The marks on the loading surface showed that the last items of the load at the rear of the vehicle had slipped forwards by up to 2.5 meters. In Diagram 1, we have shown how the load had probably originally been loaded. A number of material handling trucks, all in a neat row; at the front-right a lifting mast "packed" in two wooden clamping pieces and two or three more pieces of loading equipment:

Diagram 1 [Wolfgang Jaspers]

Figure 2 [Wolfgang Jaspers]

Figure 2 gives an indication that the load has slipped forwards by a considerable distance. We can only guess exactly what the securing arrangements on the loading bed were. At this point, we would like to highlight the reinforcement slats in the tarpaulin, which indicate that this vehicle is authorized for intermodal operations. This is confirmed by the yellow label that can be seen in Figure 3:

Figure 3 [Wolfgang Jaspers]

Figure 3 shows the state of the vehicle after the emergency braking maneuver. The load slipped forwards, penetrated the tarpaulin at the front-right and "only" caused the tarpaulin to bulge on the left of the vehicle.

Figure 4 [Wolfgang Jaspers]

Figure 4 clearly shows that the load has become "compactly stowed" as a result of slipping forwards. The mast with its forks probably accounts for one of the tie-down lashings, possibly even two. It was not possible to reconstruct this precisely after the event. But it is of no significance, since the emergency braking maneuver provided proof that the load was inadequately secured. On the basis of these photographs alone, we are also largely unable to judge to what extent this lifting mast and its forks, of which we do not know the weight, was packaged in a way that it could be transported safely, and we prefer to make no comment here. The entire chain of events (the whole of the load concertinaed) resulted in damage to the load, which may have survived intact if only it had been secured properly.

It can be clearly seen that a mixture of direct lashings and tie-down lashings were used. The direct lashings appear to have been used as tie-down lashings. As a result of the fact that the load slipped forwards, these lashings at some point adopted a position where they acted as genuine direct lashings and prevented the load from slipping any further. This can be seen clearly in the last photo (Figure 9) of this Photo of the Month.

We shall not discuss in detail the securing arrangements and any preparations that had been made, since we can, as we have said, only partially reconstruct how the load was secured. Nevertheless, we can definitively establish that the orange belt, or what is left of it, that can be seen on the loading bed in the foreground of Figure 4 has obviously been cut through cleanly. Not only therefore were the securing measures less than effective; the belts had also clearly been placed over a sharp edge. And when the load slips as much as this one did, the belt has no chance and simply fails.

If we ask ourselves whether anti-slip mats were used with this load, the point should be made that there was little need, at least in the case of the material handling trucks. This is because the trucks were new and were all fitted with pristine rubber tires. And the loading bed was clean. This would have made the use of anti-slip mats redundant, provided that the brakes were engaged on the trucks. (Having said that, anti-slip mats would still not have generated any securing effect if the brakes were not engaged.) And we are also not in a position to say whether anti-slip mats would have made sense for the lifting mast that penetrated the tarpaulin on the front-right.

Figure 5 [Wolfgang Jaspers]

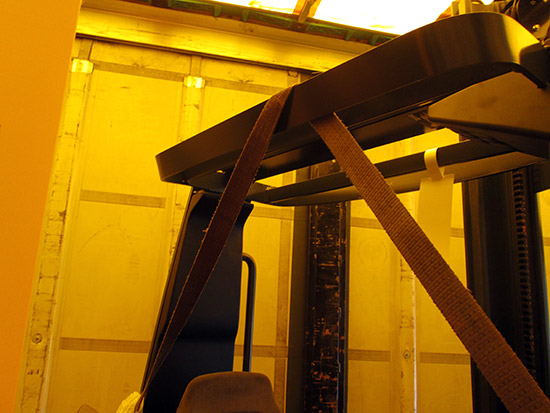

Even for us as experienced load-securing columnists, it is exceptionally rare to see a belt attached in the way we see in Figure 5. The advantages of this method of attachment are undoubtedly that the belt cannot be stolen and that it does not become detached when it is being tightened. But that exhausts the possible benefits of this attachment method.

Once the decision has been taken to attach the belts to the vehicle using a bolted metal bridge (after ensuring, of course, that there are no sharp edges), these belts can only ever be used for tie-down lashings. In 99 % of cases, a direct lashing would not be permitted, as this belt can only be used laterally, i.e. at 90° to the vehicle frame. This photo speaks volumes: As we have already seen in the other photos, the load has slipped forwards massively and the belt is now asymmetrically loaded, i.e. it will lose a considerable part of its strength, as it is subject to a tearing load.

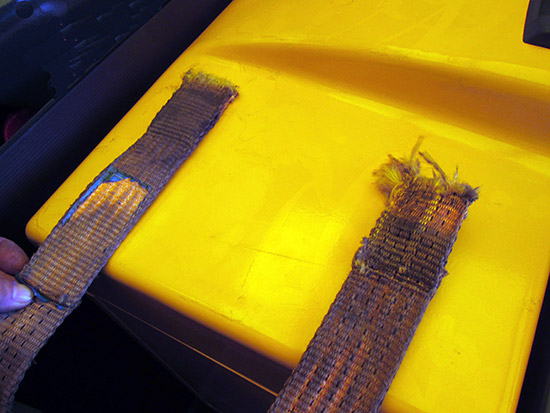

Figures 5a and 5b [Wolfgang Jaspers]

Figures 5a and 5b reveal a further bolted metal bridge (see arrow). This is where the belt was attached that can be seen in Figure 5b. Here again, the slipping load also inclined the belt and subjected it to an uneven load. And then the fibers of the belt gradually failed, one by one, from the outside to the inside as the belt was loaded obliquely in this clamp. If you want to ensure that the belt does not slip off when it is being attached, you can use hooks fitted with magnets. These make sure that the belt stays in the right place. (Hooks like this are available on the market.) Hooks have the major advantage that they turn in the direction of loading and the belt is always loaded evenly at the point of attachment.

Figure 6 [Wolfgang Jaspers]

Figure 6 shows a pallet that was probably used to transport the loading unit. When the load slipped and concertinaed, the pallet was almost completely destroyed and the housing of the loading unit at the very least shows signs of deformation.

Figure 7 [Wolfgang Jaspers]

The belt that can be seen in Figure 7 was probably used as a tie-down lashing. We have to ask ourselves, however, why direct lashings were not used everywhere, given that the load was brand-new equipment that generally weighs a considerable amount. Items with a weight of 2 – 4, or perhaps even 5 tonnes, are difficult to secure with tie-down lashings. And the same is true even for items with a weight of just one tonne. As a rule, forklift trucks and material handling trucks provide plenty of opportunities for direct securing, and we have to ask ourselves why these were not systematically used. Some loader loaded up this vehicle and sent the driver onto the road with a disastrously secured load like this. If this braking maneuver had happened in a bend and the whole load had slipped to one side (and possibly fallen from the loading bed onto the road), the consequences may well have been far more serious.

Figure 8 [Wolfgang Jaspers]

Figure 8 shows us more belts that were either sliced through by the load itself or torn out of the clamps described in detail above. Belts like this have hardly any securing effect while the load is moving, as they tear to pieces even under relatively low loads.

Figure 9 [Wolfgang Jaspers]

Figure 9 gives a good impression of how the load has become entangled as it slipped forwards. Belts that had initially been attached as rather halfhearted tie-down lashings became direct lashings as a result of the considerable movement of the load, and these "indirect" direct lashings then actually did their job. The material handling truck that can be seen on the right is standing at an angle because the single original tie-down lashing has become a direct lashing and is restraining the load.

So why not do this to start with? Why was this not done for the entire load, and why did the loader (who, we assume, had some degree of interest in this load of new equipment) allow this vehicle onto the roads in this state? We hope that the police officers who responded to this accident will take action against the loader as well as the driver. And we do not do so out of malice, but rather in the hope that it will act as a wake-up call to all those responsible for loading this cargo. Perhaps they will begin to think how a valuable load like this, that could become a deadly hazard for all other road users, can be secured properly.

Your load securing columnists as always wish you a safe journey!

Back to beginning